“I was in bedrooms at four in the morning watching Liam and Noel hammer each other, y’know!”

Paolo Hewitt definitely “was there then.” For four crucial years he was at the centre of Oasis’s inner circle. Working as the band’s DJ he saw first hand the incendiary power of the original line-up at era-defining shows in front of tens of thousands of people. Paolo also had exclusive access to the unfolding dramas as their fame exploded, in dressing rooms and in recording studios, watching moments of creative success and also familial tension. Written from that insider’s perspective, his two accounts of life with Oasis are the definitive telling of the Oasis story. Getting High, first published in 1997 and newly available as an e-book, takes the band’s story from childhood to Knebworth. The Be Here Now world tour is chronicled in Paolo’s second Oasis book, Forever the People, and finds life within the inner circle to have changed greatly. In this exclusive interview for Oasis Recording Info Tom Stroud hears from Paolo Hewitt about the highs and lows of his time with Oasis and also the creative processes involved in writing his books.

Tom: Oasis are a brilliant subject for a biographer and right up your street: rock ’n’ roll, working-class heroism, fashion, love of football and the Beatles – it’s a great story isn’t it?

Paolo: I know and, yeah, I’m a sucker for all that! I’m always attracted to those kind of stories and this one was perfect. And also because Oasis became such a phenomenon between ’94, ’95 and ’96. That put the icing on the cake, as it were. I mean there’s kind of other bands a little bit like them, but none had the incredible success that Oasis had.

It was a special time and your books do present that: they are very vivid, with pacey narration and an almost novelisation of some parts of the story.

You’re very astute. One of the books that had a real impact on me when I was a young man was In Cold Blood, by Truman Capote. And that led me on to all the new journalism stuff like Tom Wolfe (the New Journalism anthology), Hunter S. Thompson… and that was all about taking journalism away from being cold and factual and using novel-type techniques within it. Which I really liked doing because it just makes the story much more exciting, really. And it also gives you much more of a flavour – if you’re trying to describe a character, a situation, a record, or whatever it is. So I’ve always enjoyed that very much and it’s one of the things I’m very interested in.

That sense of “being there” runs through your writing. Getting High is almost cinematic – it’s not chronological but jumps around a bit to put you in the place.

Yeah, well that’s another thing: film is a big influence on me as well. I’m a big fan of films such as Once Upon a Time in America, which use flashbacks in a very creative way. That kind of stuff [in Getting High] came with the times as well. They were heady times: there was a lot of drink around, a lot of drugs, and [the prose style] gives you a sense of that as well.

Getting High is the definitive account of the early Oasis story. It isn’t an “official” biography but it had input and support from the band, their families, and management. How did you come to be in the position to write the book?

What happened was that I went to see Oasis – they played two London gigs in a week: one on the Tuesday at the Kentish Town Forum [16th August 1994] and one on the Thursday at the Astoria, I think [18th August 1994]. And after the Astoria gig I went to an after-show party and that’s where I first met Noel. He knew about me because he was a big Jam fan and I’d written the official Jam book. So he knew who I was and we had a very brief chat.

And I was really knocked out with them because, at that time, their sound was so big and yet they were so static; it was such a weird dynamic to see this band with such a huge sound and them just standing there, not moving to the music. And they looked like a gang as well. So visually they were compelling, and musically they were compelling; Liam’s voice was completely different to anything that was around at the time and Noel’s songwriting was obviously in that classic rock and pop tradition. So I was quite taken with them.

And then in the January I got a phone call from Noel and he said, “Look, I’m in this flat in Fulham”, which turned out to be Johnny Marr’s flat, “…d’you want to pop over?” And I said yeah, I’d love to. So I went over and, y’know, it was like you just said earlier: Beatles, football, that kind of thing.

When I did the book I went to Noel’s house in Burnage, where they grew up. And it was just like the council house where I’d lived in Bisley after the children’s home. I was sitting there going: “This sitting room is exactly the same!” So there were a lot of similarities, as it were. And then I got to know Noel very well. Me and him hung out a lot in that year. And it was an amazing year, ’95, because everything was fresh to them; everything was new. It was like, “Oh my god we’re going to Japan! It’s fuckin’ amazing!” And, as Noel pointed out to me, in just one year they’d gone from playing a pub in Yorkshire to playing the Sheffield Arena. It was such an incredible ascent, and I was there. I thought that it really needed documenting, so I approached them and Noel was really up for it.

But it was Marcus [Russell, Oasis’s manager] who said he didn’t want to make it an official book because I think, at that time, there were other [Oasis] books coming out and I don’t think they wanted to get on the bad side of the other writers, [implying] “We’ve chosen Paolo and not you guys.” I think it was that. And the fact that – the official one – if Noel ever does his book then he will command loads and loads of money for it. So I think it was a business decision, which I was fine with because I had complete access anyway. It didn’t really matter and everybody was more than happy to talk to me.

Well let’s talk a bit about that access. Because, like you said, when you joined the party that’s early 1995. So already there’s a bit of back story to fill in. And that involved research, and also sitting down and talking to people. Can you tell us a bit about the research process?

Because I was spending a lot of time on the road with Oasis I had a very good friend of mine called Beatrice, [Beatrice Venturini in Getting High’s Acknowledgements] an Italian girl, do the research for me on Manchester. Meantime, during my time with the band, I would ask people questions along the way: “What happened when you recorded with the Real People? How did that all come together?” And also, because I’d be there in the dressing room, on the coach, and in hotel rooms, they would naturally say stuff like, “D’you remember that time we were travelling back from that gig and we got stopped by the police and they opened up the boot?” So I was just jotting it all down. So it was kind of a bit of formal research, and a bit of informal research as well.

And the great thing was that Noel asked me to DJ, which was really good because it meant that no-one saw me as “The Writer.” It was more like, “That’s Paolo – he’s the DJ.” No one thought, “That’s the writer, we’d better keep quiet.” So when I’d come into the dressing room no one would shut up. They would just carry on. They wouldn’t shut up in front of me for fear of being written about. So I got a load of good stuff there, really.

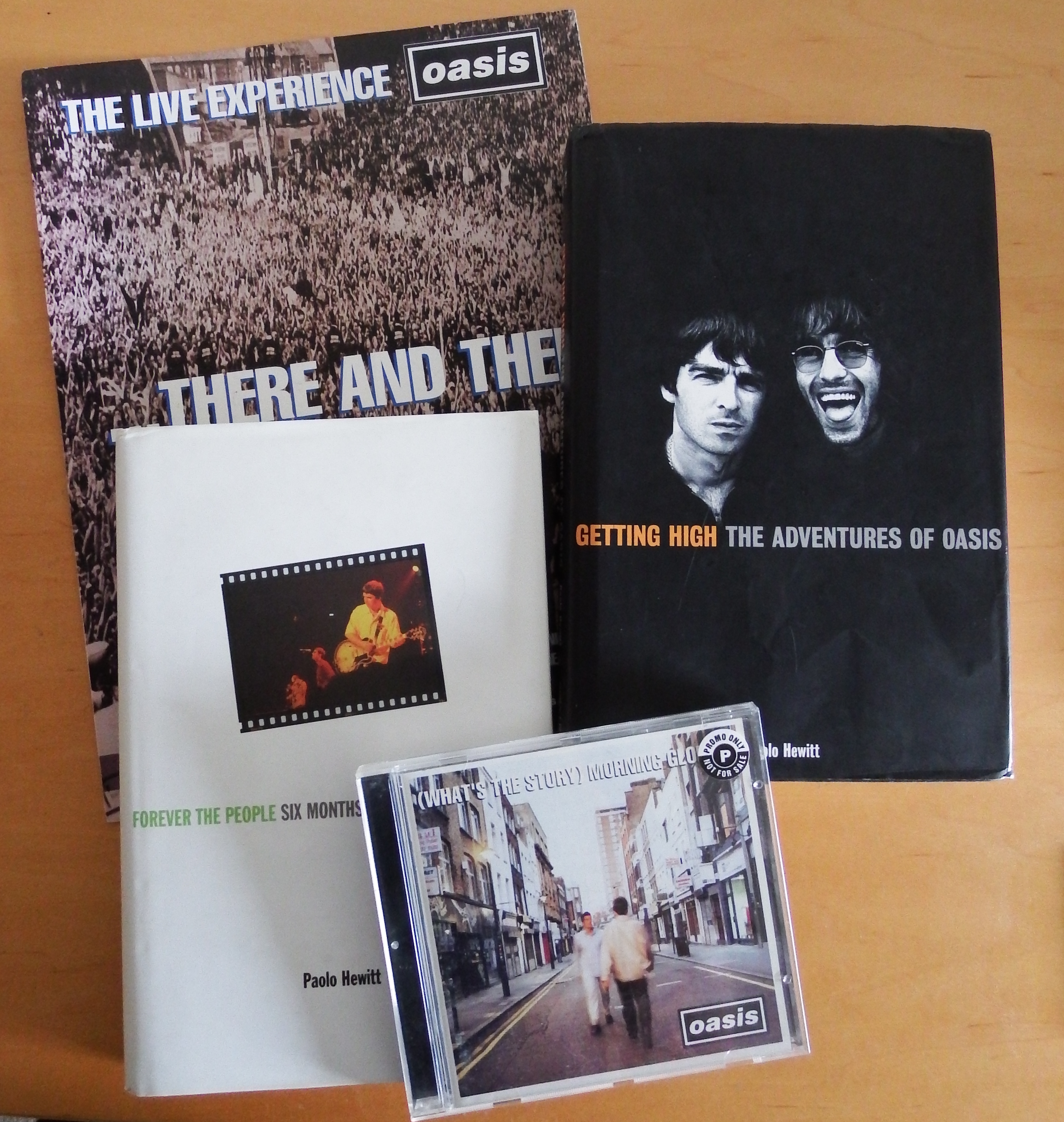

Top: There and Then press ad (1996); Middle: Getting High (1997); Left: Forever the People (1999); Bottom: Morning Glory promo CD (1995). Photo by Tom Stroud for Oasis Recording Info.

Your book is very specific. There’s a lot of dates and a lot of detail in it. You mentioned that earlier, presumably, you had access to tour diaries and everything was open to you.

Yeah, I did a lot of groundwork. Getting stuff from Creation Records, going through the NME, reading everything about them. I think I spent probably January, February, March [1996] just reading. It was important to have all that documented, like: “They played here, they did this, this is where that happened, this is where that happened.” So that took me about three months really. And then I thought, “Well, I’ve got enough info now.” Like I said, I had a great mix of the formal and the informal to work with. I do think with any biography, and also just personally, I wanted to up my writing. A lot of people really loved The Jam: A Beat Concerto but I think it lacked a lot of detail. Because, in that time, in ’83-’84, detail wasn’t such a big thing as it is now. And if I did that book again I’d put [things like], “They went to RAK Studios on 12th October and this is what they recorded, and da-de-da-de-dah…” And that’s what I was trying to do with the Oasis book. To up my game, just as a writer. That, to me, my books up to [Getting High] are kind of stepping stones to the one where… that was my Morning Glory, if you like!

You’d already written books on The Jam (A Beat Concerto) and the Small Faces (The Young Mods’ Forgotten Story) – but they were kind of ‘closed’ stories because you knew how they ended; Getting High was different in that it was an on-going story, wasn’t it?

Yeah, It was! It was. And I did a follow-up to it when I went on tour with them [Forever the People]. Which I always liken to that Beatles book from ’63…..

Michael Braun’s Love Me Do.

Yeah. [Forever the People] was more about what it was like to be on tour, really. I think there’s a lot of good scenes in there because obviously I was in bedrooms at four in the morning watching Liam and Noel hammer each other, y’know! [Laughs]

Let’s talk about that. The fact that you’re in the dressing room at four in the morning and there’s certain craziness and substances going on, and you went and wrote it down the next day. Which-

No, that night!

What, before you went to bed?

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah!

Because there’s a huge amount of discipline in all of this, isn’t there?

Yeah, well I had to be, I had to be, because – even though it was great fun – I would get back to my bedroom and I would just think: “What did Noel say about that? Liam said that, Guigsy said that,” Crrrr, and I’d get it all down. I’d wake up in the morning and I wouldn’t be able to read my own writing! Haha. Nah, that’s not true! But I knew it was an important book. And so, even though, yeah, I had a few drinks and whatever, there was always part of me which was like: OK… just remember what they said, y’know. So I was able to do that.

Were you the guy with the notebook, or did you have a cassette running…?

No. No, no, no. I had all these big green notebooks back at the hotel. So when I got in I would literally spend an hour just scribbling everything down. That’s if it was of interest. Some nights nothing happened! And it was boring, y’know? And other nights I’d get a load of really good stuff.

The account of the set-to between Liam and Noel at Maison Rouge is particularly vivid and a brilliant way to open Getting High. How did you go about writing that chapter? The dialogue seems completely authentic. I thought that was a transcription of a cassette or something.

No. No, no. It was… I mean… I got home at 4 a.m. after that one and I probably spent about two hours writing down everything I could remember. Because that’s one of my favourite tracks, The Masterplan. I think it’s probably my favourite Oasis track. And hearing that for the first time… and also Round Are Way as well. But hearing The Masterplan and thinking, “My god, this is epic!” And Noel’s writing had just got better and better and better, d’you know what I mean?

I mean, I like the first album but it seemed he was just getting better and better and The Masterplan was that… I was just excited when I got in. I thought it was just amazing. I think I got him to play it three times: “Play that tune again!” [Laughs] It is such a wonderful record.

And a stunning way to open the book because it really sets the tone as well.

Thank you. When I came to write it I knew, straight away, that that scene had everything: Noel’s songwriting, Liam bickering, Meg was there… a lot of the people who were around the group at the time. I thought it just set it up really nicely, and there was that big argument, but then Noel plays The Masterplan and it just shuts Liam up! I just thought: this is brilliant. Those things fall into your lap and you’ll be, like, “Thank you Lord.”

So you started DJ-ing for the band at gigs and you’re making notes at the time. Once it became clear that you were writing a book did your relationship change? Were they suspicious or guarded around you?

No, no. They knew that I was… I mean, at that point, they didn’t care. They really didn’t care. I remember having a meeting with Marcus and Noel, and Noel was saying [to me] “You write whatever you like” and Marcus was like, “Noel, in ten years’ time you’ll have a kid; are you sure you want them to be reading this stuff?” Noel was saying it’s not a problem. I think now if I was to say to Noel, “Can I do a book now about you?” he’d probably be a lot more guarded. But then… that’s what I was saying to you: it was such fun, because everything was new to them. They’d come from literally playing to two people in a pub to Earls Court. What a journey! In, like, a year and a half.

I never had any problems with any of them really. It wasn’t that… I mean there was a lot of rumblings from some of their friends, like, “Who’s that fuckin’ cockney?” D’you know what I mean? I’m not even a cockney! But there was a bit of that Manc… a lot of, “Fookin’ cockney fookin’ who’s he fookin…” blah blah blah blah blah.

Like you wouldn’t understand because you’re not from the North.

Yeah! Cos Mancs are like that; they hate London. But I used to get them by doing this thing: “Er, Liam, where do you live?” Primrose Hill. “Noel, where do you live?” Belsize Park. “Guigsy…?” and so on. When they were giving their, “Manchester was the be-all and end-all of everything” thing I’d just shoot ’em down like that. [Laughs].

They couldn’t wait to move out though.

And also football was a big thing as well.

Yes. Of course!

But I’m Spurs, so I’d just mention Ricky Villa (who scored the winner in 1981 for Spurs against Manchester City in the FA Cup final)… that’d shut them up! For a second. So everything was just fun. Everything was just happening, like, crazy. And I think they were far more open, so they really didn’t care. And they knew they could trust me because they knew that I was a fan of the band and that I wasn’t… you’ve gotta remember that Oasis were very, very clever in the early days. Because what had happened was that, in the eighties, the inkies – the tabloids – had got interested in pop music again. And so: here’s Boy George, and isn’t he cuddly? And isn’t he lovely? And… CRASH! He’s a heroin addict. Crisis! Blah blah blah blah blah. All that.

So what Oasis did was that they came along and went, “Yeah, we love cocaine, we love girls, we love drinking, we love the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle” …and what could [the press] do with that? There were no great exposés to do on the band because they’d fessed up to it already. I remember seeing this headline in the News of the World where, I dunno, one of their bodyguards had written a book and it said something like: “Liam Took Two Grammes of Coke And Climbed On Top Of A Coach” or something and all the country said: “Yeah, we know! He told us that last week.”[Laughs].

Yeah!

So they said we know that because they’ve told us this. There’s no, y’know, there’s nothing to expose.

I remember reading a quote from Noel and this was like ’94 or ’95… Oasis were a group who unashamedly wanted it all and Noel in particular would tell fans, “We tell the truth, we’ve got nothing to hide.”

Yeah!

Did that mean there were no restrictions on you as a writer?

Yeah, yeah, yeah! Because what was I going to say that the tabloids hadn’t already said?

Yes.

Y’know, there was nothing there. So… I think there’s one bit where I’m round at Noel’s flat and he deliberately picked an argument with Liam so that Liam would shoot off in a rage. And Noel just pulled out a wrap and went: “Great! More for us.” [Laughs]. And he’d done it deliberately. And I wrote that and they were absolutely fine.

The scenes of the Gallaghers’ tough childhood and home life are particularly evocative. Was it hard to talk to Liam and Noel about that sort of thing?

I was brought up in a children’s home you see; so I kinda knew that shit, d’you know what I mean? So I could kind of… when me and Noel were drunk one night and I said, “Look, I know you’ve had shit in your life but I’ve had shit in mine.” And that kind of binds you. So I think they realised that what I would do would be sensitive towards that. But I kinda knew that world anyway; I understood their relationship with their dad, I really did. Because I’d had a similar thing myself. My foster mother was a cruel, vindictive woman. So it was a very unspoken thing, but I knew I could write it and write it well, and it would be fine.

Your first gig as DJ (Southend-On-Sea Cliffs Pavilion, 17th April 1995) was Tony McCarroll’s last with the band. [1] Was it particularly memorable?

No, it wasn’t that great to be honest with you. I wasn’t that blown away. I remember seeing them at Brighton [29th December 1994], which was a lot better; that Kentish Town Forum gig when I first saw them was great; Blackpool, the first date of one of their tours, [2nd October 1995] was amazing; one in Aberdeen was fuckin’ out of this world [20th September 1997]. But, no… I mean it was all just chaos. There was this real sense of chaos going on. And then up in Scotland, what was that one where I played Hey Jude afterwards? Then everyone wrote about it and Noel was like, “You got more publicity than I did!” [Laughs]

Irvine Beach (14th and 15th July 1995) – that’s the gig you were thinking of.[2]

There you go!

What was it like DJ-ing, seeing the crowds?

It was fantastic, it was great. What was interesting as well – just culturally and musically – was that in the eighties I only really listened to black music. Because, for me, rock music was just rubbish. All these indie bands and… y’know, it was just dire. And then suddenly you had acid house, which was amazing; and you had hip-hop, which was amazing. So, at the NME, I was known as the kind of black music guy, like: “There’s Paolo in the corner with his disco stuff.” I was known like that. But in the ’90s when I went… there was this real sea change. Because bands like Oasis came along. All these bands started appearing who’d been part of that thing; they were into hip-hop and they were into acid house. In fact, did you send me that track that was close to Columbia?

David might’ve done. He might’ve got one from me.

He sent me this track that influenced Columbia [Axe Corner – Tortuga], and it’s this pure acid house track.[3] So it was this melting of all those barriers. That’s what I loved about the ’90s – all those barriers went down and I think ecstasy had quite a lot to do with it. I remember being at the NME and all the writers coming back from Glastonbury after seeing the Stone Roses or someone, and they’d all done an E… and suddenly they were coming up to me and going, “You know that track that goes: ‘Can you feel it?’ – who’s that by?” I’d go, oh that’s so-and-so [Fingers Inc. – Can You Feel It]. And then another one would come up. So all those barriers were broken down I think. So when I was DJ-ing I could play anything, as long as it was good. You could play Hey Jude and you could play Sly Stone; people would get off on that as well. There was this real sense that anything could go. It was a very exciting period, musically.

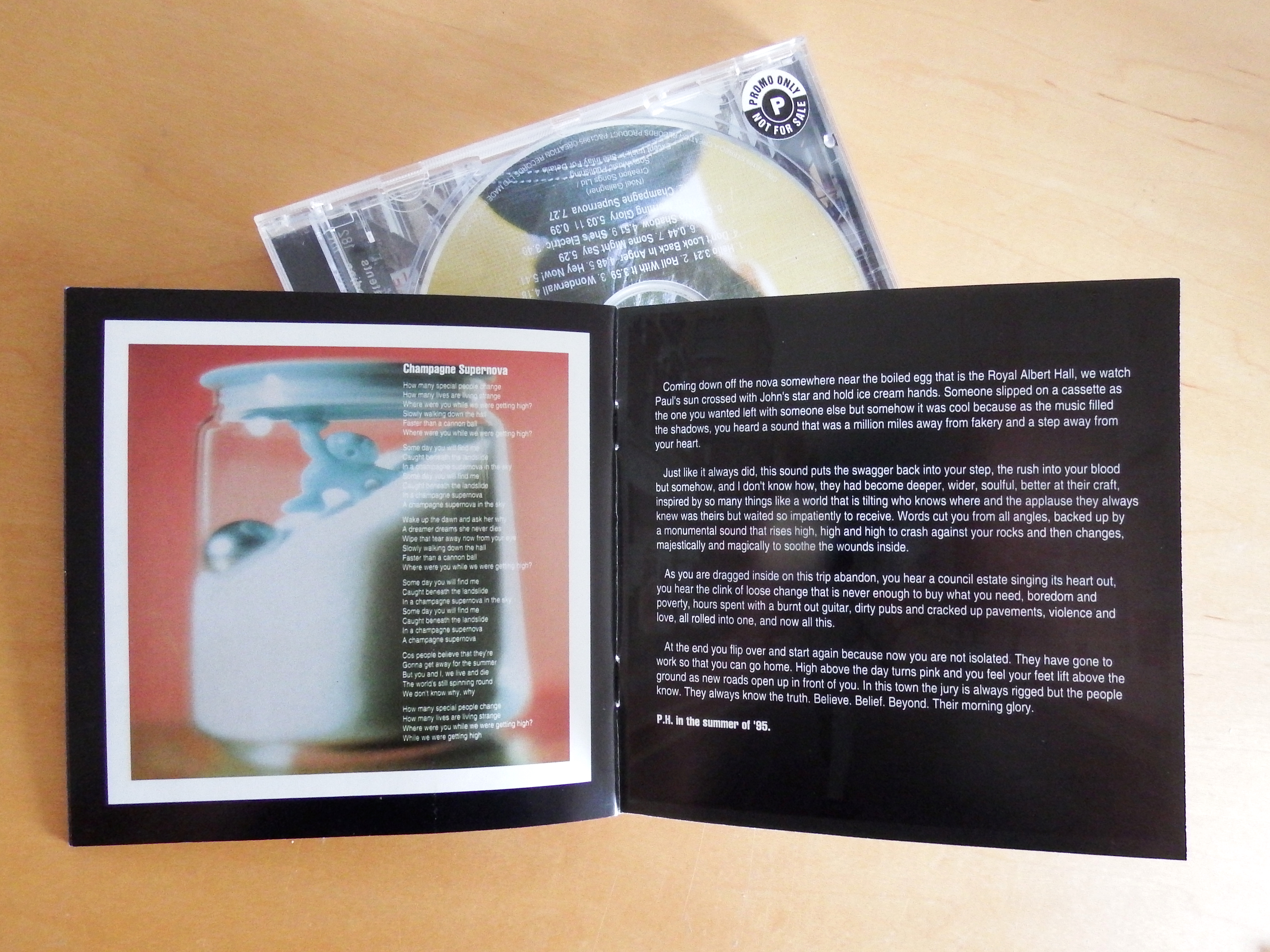

Morning Glory liner notes by Paolo Hewitt. Click to view full size. Photo by Tom Stroud for Oasis Recording Info.

In summer ’95 you wrote the liner notes for Morning Glory, describing Oasis as “A sound that was a million miles away from fakery and a step away from your heart… a council estate singing its heart out, you hear the clink of loose change that is never enough to buy what you need, boredom and poverty, hours spent with a burnt out guitar, dirty pubs and cracked up pavements, violence and love, all rolled into one, and now all this.”

Which I did Sunday morning at 9 a.m., absolutely sober at my sister’s house in Horley, Surrey. And everybody was like, “You were off your tits!” but no – I was absolutely stone-cold sober! [Laughs] But I thought that it needed a kind of surreal sort of thing in there. There was no point in writing a kind of, you know, “This band are from Manchester” and blah-blah-blah… I thought I’d just go with the flow. And I was absolutely stone-cold sober when I wrote that.

It’s like a surreal love letter to the band, isn’t it? Because you were clearly a fan!

Yeah, it was. And, y’know, they’d asked me to do that and I was very honored to do it.

How did writing the liner note come about? They’re rare for albums (Morning Glory is certainly the only Oasis album to have one).

Well, the old ones did… Noel just came to me and said, “Do you want to write it?”

The Beatles albums did, but I assumed it was a nod to the mysterious Cappuccino Kid’s missives on Style Council sleeves…?

Well, there was a little bit of that going on as well, I suppose. I remember being in America and three or four people were like, “Oh my god, I really love that piece of writing.” There was one girl who said, “You’ve made me a poet because of that.” And I was like: “I really do apologise.”

You wrote the Morning Glory sleeve note as “P.H.” Why the initials?

Because every time I write something for an album I always like to put a different name.

Oh OK. And you’re listed, P.W. and P.H., with “eternal respect” to you both.

Yeah, yeah. Which was beautiful.

Was objectivity ever an issue in writing Getting High? You loved the music and were also employed by them… did you ever think: I better tone it down a bit because this is turning into too much of a love letter?

I dunno. Well… I liked all that stuff up till then. It’s the first two albums, isn’t it?

Yes.

And so, y’know, I didn’t think they’d put a foot wrong, really. But then I’d heard that stuff about Whatever where they got sued by Neil Innes didn’t they?[4] And then the Coca-Cola thing as well [with Shakermaker]. But, you know, people used to go, “Oh, the beginning of Don’t Look Back in Anger is John Lennon.” It was deliberately John Lennon. It was put there to wind people up! That’s what they were doing, like: “You think we’re ripping the Beatles off? Have a listen to this!” [Laughs] It was like, they didn’t care. All musicians before always try and hide their tracks; they nick a riff and then try and hide it away. Oasis didn’t. They just played up to it.

Cigarettes and Alcohol is audacious isn’t it? You wouldn’t do that now – it’s such an obvious nick.

Exactly. And they got sued – and they didn’t care! It was like, “Yeah, give ’em money, who cares?” That’s how it was. It was so refreshing.

You interviewed all of the band on camera for inclusion in the “There And Then” video. What was that like?

That was great. They were all very comfortable with me. By this time I’m going to Guigsy’s house, Noel’s house, occasionally seeing Liam. It was such a great time. I’d go round to Noel’s flat in Camden. I always liked that line in the book where I said his success was much bigger than the flat. [Laughs] It was true because they were so big by then; and yet you’d go to this tiny flat in Camden. And we’d watch the football and stuff like that. And it was all just a laugh. So they were very comfortable with me. It was all good.

There’s that George Harrison line about the calmness at “the eye of the hurricane” – you were in the middle of it, weren’t you?

Yeah, yeah. And also because they kind of… the Beatles said it, didn’t they? In that the one they felt sorry for was Elvis, because at least when it happened to the Beatles there were four of them who could experience it together and protect each other. Whereas Elvis was completely on his own.

Being part of the gang makes the difference, doesn’t it?

Yeah. Absolutely. And Oasis were very much a gang then. I think my favourite photograph of them was a little bit later on, for the Be Here Now thing. And Liam’s obviously just said something mad and they’re all just pissing themselves laughing. D’you know that one?

Yeah, is it Jill Furmanovsky’s shot?

Yes, Jill’s – that’s my favourite shot of them man, because they did come out with these surreal things. It was very much… I mean Noel was always full of stories. And he would always elaborate. So I remember going round the flat once and he’d just seen Morrissey in the street. And it wasn’t like, “Hello Morrissey. How are you?” It was huge, kind of, “passing of the flame to Noel” [symbolic] kind of stuff and I remember thinking: yeah, right! But Liam would come out with stuff like, “This place smells of balloons.” [Laughs] I was like, “What?!” He had this kind of surreal kind of sensibility. And that kind of informed the sleeve notes as well. That’s what I was trying to capture.

Tell me about the rest of the band – Bonehead, Guigsy, and Alan.

Well they were very much the… they knew that Noel and Liam obviously were Oasis. And they were very, very protective. And they were really lovely guys, very loyal. And very funny as well. Bonehead was funny. Guigsy was more of a spliff man, so he had a much more dry sense of humour. I remember we played football once in Australia and I was playing up front. And I thought I could smell something… and I realized he had a fuckin’ toke going on! [Laughs]

But, for example, that football game was on the Be Here Now tour. And by then it’d got too big. And Liam had gone out and smacked a fan in the mouth, d’you remember all this?

That’s right. I remember – this is in the book, isn’t it?

And it was… we were all woken up and it was, “Don’t talk to the press” and it was all this crisis thing. And Guigsy went, “You see that park over there? We’re gonna go over there and have a game of football.” And everybody was like, “Uh, what?!” And he said, “Come on, we’re gonna have a game of football.” And everybody went over and we played some local side and we won. And Guigsy had bonded everybody together; he’d brought football in and bonded everyone. And that night, everybody was back and it didn’t matter what Liam had done. And that’s what I mean about their kind of loyalty: they were clever in knowing how to protect each other.

Bonehead seems a stabilizing influence at the time.

He was great, Bonehead. Yeah, that’s what I mean. They were stabilizing and they knew everybody inside out. So they could… when mates know that they know how to protect each other. So it was a great thing.

In writing the first book you interviewed a lot of the band’s then inner circle as part of the research process – can I throw some names at you and just get you to give a sort of potted reaction to them?

Yeah.

Alan McGee.

I didn’t really know Alan. He used to turn up on gigs and I think he was a bit wary of me and I was a bit wary of him. But then I said, “I really need to talk to you for the book.” And then we really bonded. You know, music brings people together. If you’ve got a love for music it doesn’t really matter what the music is. And that’s why he asked me to write the Creation book later [Alan McGee & the Story of Creation Records: This Ecstasy Romance Cannot Last].

And I really like Alan. He’s very funny, very self-deprecating. He’d got a very good grasp on what was going on. And he loved the band, he really did. And he’s always been a very big supporter of the band, he really has. Very loyal.

Marcus Russell.

He was a great manager for them because he had this calmness… he didn’t panic. He wasn’t a panicker. So when things went mental he took control of the situation and made sure it was OK. And he had a very self-deprecating manner.

There was a lovely time once where me and Noel went to Italy. And that’s when I interviewed Marcus, in Italy. I kept on asking for an interview and he said, “Look, I tell you what: me and Noel are going out to do a couple of radio stations in Italy for a couple of days, I’ll probably have a bit of time then; why don’t you come over? And we can talk then.” And that’s when I got a really good interview from him. He was a lovely guy Marcus.

Very straight, very sober sounding when you read him talk.

Yeah, well he had to be because [Laughs] everybody else was lurching around, weren’t they?

Owen Morris.

Owen was fine but I don’t think we really… he didn’t kind of get me because when I showed up… I don’t think I interviewed Owen, and I kept meaning to but it didn’t happen. And he couldn’t quite work out what I was, because one minute I was a DJ and then I’d written an article. He couldn’t kind of get a grip on me, y’know? So… but he was fine, he was fine.

The Real People – because that’s an interesting story in itself – did you interview them?

Yeah. They played support on a few of the gigs. So I got to know them. Of course they kept on bugging me to write their book! [Laughs]

Because they’ve got their own tale to tell about what happened in the early years, haven’t they?

Yes. It was only afterwards that – I think it was Tony [Griffiths] said to me that he felt that… because one thing which I never nailed and it kind of… even now thinking about it kind of bugs me – was that, if you – d’you remember those Oasis demos that came out? The first lot?

Yeah, the pre-’93 ones: Colour My Life and all that stuff.

How bad were those songs?

Yeah, they don’t sound like the Oasis of ’93.

They’re dreadful, right? They’re absolutely dreadful. How did they go from that to Rock ’n’ Roll Star or all those other tracks? How did Talk Tonight or… how did all that come about? And Tony says that Noel was cadging a lot off the Real People. And he probably was, I don’t know. But it’s one thing that bugged me and I should’ve nailed that a bit further, really, in the book.

I think there was some legal action, wasn’t there? Because the Griffiths do get credits on certain records now when they didn’t at the time.[5]

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I should’ve kind of gone in a bit on that. And it was one thing I thought, “I must ask Noel how they went from one thing to another.” But he probably would’ve given me some bullshit answer. Because, really, he was just developing, do you know what I mean? But it is incredible how that… because those first eight songs are dreadful.

Yeah, they’re baggy, shuffly; they sound like Northside. They don’t sound like the Beatles, do they?

Yeah, yeah… Northside gone Southside! [Laughs]

The Abbots! Tim and Chris – they were a force at the start of the Oasis thing weren’t they?

Yeah they were. And Tim was – I didn’t see Chris so much – but Tim was really funny. He made me laugh… I remember him saying to me once he had a job at Levi’s. Where he was doing advertising or marketing for Levi’s, and he said, “I went to Thailand and I didn’t come back for two years.” Pause. “Those pills are good aren’t they?!”

And Johnny Hopkins as well, doing the press.

Well Johnny made me laugh man because by this time, by ’95, I was really close with Noel and I remember Loaded had said to me, “Look, can you get an interview with him?” So I rang Noel up and said, “Are you up for doing an interview for Loaded?” And he said, “Yeah, come round – we’ll do it now.” [Week of release of Roll With It single, August 1995].

And, of course, I went round there and we did the interview about the album… and we went to Regent’s Park and this photographer came along, took some photos. The photo was of the ball coming in, flying in front of Noel? The football?

Right, yes.

Yeah, that’s in Regent’s Park. In fact that’s me kicking the ball. And then I went home and wrote it. Didn’t even think anything of it. Just sent it in and, of course, it was the front cover on Loaded and it wasn’t part of their press campaign. And suddenly there was… all hell broke loose. People were so precious about everything. And I remember Johnny saying to me, “I think that this interview could’ve well and truly scuppered the sales of (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?” [Laughs] Eleven million albums later…

Didn’t do any harm! But of course you had the direct line to Noel at the time; you didn’t have to go through the press department.

Yeah. I can see Johnny’s point of view really, but he was… and they were very clever as well. That first interview with the NME [published 23rd April 1994] – they’d talked about it beforehand, like, “It’s our first NME interview; how are we going to handle this?” Well, you know, why don’t you two have a ruck? And that kinda set the tone, didn’t it?

That’s the Wibbling Rivalry interview.[6]

Exactly. Yeah, yeah. And it was like that; you can imagine them in their bedroom at sixteen, shouting at each other about songs being better than… because Liam was convinced that the way he looked and his attitude was what was drawing people to Oasis. And Noel would say, “No, it’s the fucking songs”, you know. So…

And that charisma: a joy for a writer as well.

Yeah, because that tension went the whole way through. I think there was a bit in [Getting High] where we played Dublin [23rd March 1996] and their dad shows up and Noel’s like, “Don’t fuckin’ talk to him!” [Noel and Liam] used to do this thing where they’d lock – like Antelopes, you know? They’d put their foreheads against each other like that. So it was just – back to the hotel room crrrr, write, write, write, write, write, you know? That’s how it was.

One more name to throw at you and that’s Peggy Gallagher.

She was lovely. She gave me such a great, lovely interview. She was from that generation that didn’t want any fuss, you know. And I remember Noel saying to me, “We’ve offered her everything” and all she wanted was a bigger TV. She wanted to still live in her council house, because that’s what she knew; she was happy there. Why move? She didn’t want a big house. “We’ll buy you a place” – but she wasn’t interested.

And you went there for tea and she told you everything you needed to know.

Yeah, it was great. It was fantastic. Because Noel came with me; me and Noel went up to Manchester and we had two days there. And he took me to his mum’s house and, like I said to you, this is exactly the same as… [where I had stayed in Woking]. And there was stuff I put into [Getting High] like, there was a Formica table. And, later, you know when McGee gave Noel the Rolls?

Yes.

And Noel’s rubbing the thing going – “Well, this isn’t Formica!” [Laughs] So I made a little play on that in the book.

What was the band’s view generally on the idea of a biography? Their media image at the time suggested that they weren’t great readers…

No. And, in fact, there was brilliant day when – it was the day after Knebworth – and I’d basically finished the book. Or I’d finished a lot of it. And Guigsy said, “D’you know what? You should take it round to Liam.” Because he was a little bit suspicious. He said to take it round to Liam and show him what I’d been doing.

So Guigsy picked me up and we go round to Liam’s. And he comes down and I said, “Look, Liam, y’know, I know you’ve been a bit suspicious but this is what I’ve been doing so far. Have a look.” And he looks through all these pages and went, “It’s no fucking good to me!” And I went: “Why not?” And he said, “The fuckin’ pictures! Where’s the fucking pictures?!” [Laughs] He wanted to look good in it, that’s what he was interested in: how good he looked in the photos!

So, I think Noel, Guigsy, Bonehead, Alan White… all of them were very complimentary.

You wrote a book with Guigsy, didn’t you?

Yeah, in that same period we discovered this footballer called Robin Friday and we wrote a book about him [The Greatest Footballer You Never Saw: The Robin Friday Story] during that brilliant summer of ’96. We’d found out about this guy and we were going down to Reading together every week and finding out about Robin Friday.

How was Getting High received by management and also the publisher?

Loved it.

Were you asked to take much out? More of this, less of that?

No. Nothing. It was run as was written. The publishers loved it. I remember they let… the first one to read it was some girl from Esquire. You know that quote, “Sometimes you get what you pay for, 10 out of 10”? Whoever that was, that was the first person to read it.

There was all that secrecy bollocks as well [Laughs]. They were put into a room with the manuscript and they read it and there was… I remember Jake (my editor) calling me and saying they thought it was amazing, they love it. And there was… the only one – y’see this is the worst thing about being a writer. Let’s say I had fifty reviews of that book.

There were forty-nine going: this is amazing, this is great, this is wonderful, this is… you know… superb, and blah blah blah. And there was one crappy review and it was in MOJO. And they slagged the book off like no one’s business. And I later found it was this bloke who really hated me anyway. But that was the one review that I remembered. Not the one going, “You’re brilliant” but the ones going, “You’re crap.” That’s the one you remember! [Laughs].

But that’s the artist in you isn’t it?

But you’re just like “grr.” But, you know, you have to go with the flow and it sold really well, everybody liked it, and I’m still very proud of it. In fact the other day I dipped into it and about an hour later I was still reading it and I thought, “Fuck me! Who wrote this?! This is really good!” [Laughs].

One of my big regrets was… have you got the book there?

I haven’t got it to hand, no.

OK, well check out the first word and the last two words in the book. [“Always at it. Always. The pair of them” p. 3 and “Always at it. Always the pair of them” p. 395]

Right.

And you’ll… I was very pleased with it, except the second word I’m talking about had a letter on it which I forgot to take out. But anyway.

In writing Getting High you must have pulled together loads of interview material; do you still have the raw tapes or transcripts? And would you do anything with that?

No. I don’t think I’ve got… I mean, I’ve moved house a few times, so they’re up in the loft somewhere if I’ve got them. I don’t think I’ve got them to be honest with you. I’m terrible like that. It drives people mad… I mean, I interviewed Marvin Gaye, I should have the tapes for that but…

Damn.

But I’ve just… there were some writers on the NME who were very much into collecting stuff. So some album would come out and they would get every version of it. But – to me – it’s just always been about the music; if the music’s great then, that’s always how I’ve been. So unfortunately I haven’t got those things.

So no loft full of Oasis memorabilia or unreleased songs or anything?

Nah, well… I’ll probably have a look one day. I’ve probably got all the notebooks with all my jottings in and maybe I’ve still got all the newspaper clippings and whatever. I mean, my room was… oh man, you should’ve seen this room by the end of it. It was like Hurricane Oasis had been in there! [Laughs] It was books and things… and also because I was reading so much around, there were things like Johnny Rogan’s Smiths book [Morrissey and Marr: The Severed Alliance]. I just immersed myself in that whole thing for about two years. Which, to write a book like that, you’ve got to do.

Yeah, it’s a huge part of your life. A huge commitment.

It was, yeah. But that’s the band to do it for. At that time, that was the band to do it for. I remember when I went to hear Be Here Now at AIR Studios in Hampstead, where they were having a playback [recounted in Chapter 1 of Forever the People, pp. 25-6].

And I remember afterwards Liam going, “Yeah, I saw your fookin’ book and it was really big, so I know you’re taking this seriously.” He wouldn’t read it. He wouldn’t have read it. But because it was so big he thought that that was the kind of… and that’s right! That’s what a band like Oasis should have, a big book like that. Because they were such a big band, they should have a book as big as that.

They deserved that book.

Yeah. It was like everything Oasis did, you either understood it and thought, that’s that. Or that’s amazing, like the Masterplan, Talk Tonight, Half the World Away.

And they were so bound up in the times as well. Getting High really captures that. It’s this sense of “they’re the heroes and they win the day”, don’t they?

Well it was great because the guy who’s putting it out on Kindle (Rupert) he wasn’t particularly a fan of Oasis. And he said to me, “Would you like it to come out?”, he was starting this new Kindle thing, and I said, “I’d love it.” And I asked him if he was a fan and he said, “Nah, not really.” And then he wrote back to me and he said, “What a fantastic document of those times.” And I was really chuffed with that, because that’s what I was trying to do as well, because you had Loaded magazine; that was part of the story as well, as much as the band playing Knebworth. There were all these kind of influences going on. That’s what I was trying to do, to capture that era. And of course those things can’t last, unfortunately. But, you know what mate? It was three or four fantastic years. For me those two books, and especially Getting High, I thought – yeah – I’ve done well there.

Yeah, it was a very creative moment in British popular culture. Getting High in particular really documents that sense of joy and optimism. Echoes of the sixties were everywhere – it was a great time to be alive wasn’t it?

It was, it really was. You know I was getting towards the end of writing the book and I was so tired. And then one day I thought of this idea of Noel hitting this chord and it floating across the sea and landing where Peggy had sat (or where this young Irish girl had sat, you weren’t sure). And that kind of summed it up to me, d’you know what I mean? This whole… block of time, and what had happened. I’m always very respectful of those days, I feel that I was very lucky to be there. I really was. And I put myself there, obviously, because of the work I’d done. But I was very lucky to be there then and be there now. Or be there then! [Laughs] And to see all that was fantastic. And the summers were great and there was all this other music happening, all these other bands popping up: the Verve and so on.

Yes – Knebworth was the peak of that wasn’t it? Summer ’96. I remember it being – by then the whole Britpop thing had happened – and British guitar music was firmly back, it was a hot summer, and it seemed to peak around Knebworth didn’t it?

Absolutely. I said to Noel once (very drunk), “You should’ve split up after Knebworth. You should’ve gone: ‘That’s it, we’re finished.’” Pfft! [Laughs] Because they would’ve just gone down as the greatest thing ever, d’you know what I mean? To end on Knebworth would’ve been brilliant. But of course they had the taste for it by then so it wasn’t going to happen. If at Knebworth they’d gone, “That’s it.” They’d have gone down in history. But it carried on. I think that they should’ve at least… after Knebworth they should’ve disappeared for a year.

Yes, because Getting High ends with them going straight back in the studio to start Be Here Now. And you’re right – it was too fast wasn’t it? It was too soon.

It was. And they should’ve gone, “Lads, you’ve worked your arses off…” I mean they’d done all that stuff in America, Europe, Asia… they should have just gone: you know what? Let’s take a year out and then come back. By then everybody would’ve been gagging for something. Put a single out maybe six months in, just to keep your toes in the water. But they went back to America and there was that stuff with Liam and Patsy… all that stuff. It was just too much.

In Forever the People there’s a real sense of the band “falling from grace”- they’ve had Be Here Now, which was still a huge seller but the critics didn’t like it, and, like you say, the cynicism sets in. And your book is an account of the band’s reaction to all of that isn’t it?

Yeah, it is. And the fun’s gone. I think with Getting High there’s a lot of fun in it; you’re on this journey and it’s, “Wow, we’re on this rollercoaster” kind of thing. But with Be Here Now it was just like… they kept on talking about the old days. I found that really striking. They were talking about, “Oh, d’you remember when we played that gig when we got stopped by the law and we were all smoking spliff?”; “Oh, yeah thingy was there weren’t he…?” etc. And they kept talking about the old days and I thought this has now become a job.

I mean, that’s the thing about rock ’n’ roll, or joining a band. You join the band because you don’t want to do the 9-to-5 in a factory, but if you become really successful it becomes 9-to-5; it’s the same thing. You make the album, you tour it, you do singles, you do this, you do that, and it becomes the same thing. Because that’s what you do. So there was that sense. And also, I’d said it, that – before Knebworth – everyone got on the coach. For Be Here Now there were five cars. And they would give me a lift back to the hotel: I’d go in one of their cars, like with Guigsy, or with Noel. And it was very much… it’d just become corporate. It had just become something… Noel said to me once, “Honestly, I thought we were going to be the new Stone Roses.” On that level. D’you know what I mean?

Yes.

It was, “We were going to replace the Stone Roses.” And be very well liked, and get to play Hammersmith Odeon four nights running, or whatever. But instead they became this absolute phenomenon. It just knocked them, I mean how do you cope with that? It just became… I mean, on that tour, there were some great gigs: the Aberdeen one I particularly remember. But that was telling as well because the Aberdeen gig was in a really small place. The rest of the time it was just twenty-, thirty-, forty-thousand [capacity] arenas. And they were told they couldn’t fuck around now because there were fifty-four people on the road. It had just become a huge juggernaut. And the fun of it had gone, I think. And they go to make the next album [Standing on the Shoulder of Giants] and Guigsy and Bonehead leave.

It definitely got more corporate after Be Here Now had come out. That six-month tour was a slog because all the fun had gone. That’s what I was talking about – in ’94: “We’re going to Japan! It’s amazing – wa-hey!” But then in ’97 it was more like, “We’re not going to fucking Japan again are we? Hmmph.”

Somebody said to me… “You start off and you write a song for the pub; then you get successful and you write it for the clubs; then you write it for the Hammersmith Odeons; and then you write songs for the stadiums.” How big you get depends on what you’re writing those songs for. And that is a kind of trap, I think… I heard a track on Noel’s last album – Everybody’s On The Run – and I thought with the big chorus and everything that he’d just written that to end the set with. And I think they were just writing songs because they had to. I think some songwriters hit a patch, you know. Or some musicians… and they’re just on it: everything they do in that period, which might last a year or it might last ten years. I think the Who’s singles from ’65 to ’69 are amazing. James Brown from 1967 to ’74: amazing. Marvin Gaye from ’68 to ’75: amazing, d’you know what I mean?

Yeah, I do. I also think you’re right – you do get those purple patches. But also, you don’t analyse it – you just do it. And once you get to a certain stage it stops being instinctive doesn’t it?

Yeah, because you’re thinking, “Oh my god, 600,000 people just bought my album on the first day of release – where do I go with that now?” Absolutely. And you’re not as instinctive. And the trouble, I think, with Oasis was that they wrote songs about wanting to be rock ’n’ roll stars; they became rock ’n’ roll stars; and then didn’t have anything to write about.

Yeah.

Because they were all living in these huge houses and that creative spark where you’ve struggled away in a council house writing beautiful songs about your dreams… but once your dreams are fulfilled where do you go? And where do you go musically?

What do you make of Be Here Now? There’s a bit in the book where you make a point that your mate had said to you, look, you only like it because you know them. And then you defend it.

I think now… I loved D’You Know What I Mean? I thought that was a great song. It’s a patchy album though, it is. It is a patchy album. It worked well live at that time but it hasn’t stayed the course like some of the others have, has it? I think when they were doing that kind of rock ’n’ roll psychedelia thing (like D’You Know What I Mean?) then it was great, but then… Alan McGee made me laugh. He said, “Noel played us the demos to Be Here Now and I remember thinking… ‘Noel, I think you should maybe shorten most of the songs and not repeat “It’s getting better man” 47 times.’ Because, to be honest, number one, he hadn’t been wrong yet. He’d been right. Everything the kid had ever fucking said was right.”

In Forever The People the tone is very different. It’s a story of private planes, soundchecks, bickering, press negativity, some of the playing at the gigs is “perfunctory” and they’ve got hangovers. Within the band Noel is “pulling rank” and you’re physically threatened by Liam. Was it a brave book to write? Did you feel that in publishing it you could be jeopardizing your position in the inner circle?

Well, to be honest with you my position was kind of eroding anyway. Because it had become something different. And that different thing wasn’t to my liking, to be honest with you. And I was kind of stepping back more and more. And then when Guigsy and Bonehead left I think that was it… it just became something that didn’t interest me any more.

So the book was a kind of kiss-off to that era, really.

Yeah. Yeah, I think so.

We mentioned this earlier but do you revisit your work very often? You mentioned you dipped into Getting High.

No, no, no. It was some Oasis fact and I thought it was in the book. And I was looking through the pages and I started reading it and… one day, when I’m seventy-eight years old I’m gonna sit down and read them all.

Right, OK. So how do you feel about your Oasis books now? There’s obviously a sense of pride that you wrote them and at the reaction that they got.

Yeah, oh absolutely. Both books are very important to me. I’m really happy that Getting High is being re-published.

Yes. How did the experience of writing the books change you as an author and as a person?

It just gave me loads more confidence. There’s a writer I love, an Italian-American writer called Nick Tosches and the book that had really, kind of, that I was trying to compete with… he did a big biography of Dean Martin [Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams]. And that’s where I got the “Getting High” from.

Because I was sort of trying to – not nick his style – but adapt his style. I’m very much into the American thing and that kind of… and I thought, yeah, I’ve done it, I’ve managed to take a huge subject and people would say to me that they couldn’t put the book down. So I thought to myself, “Well, that’s 125,000 words” so, you know, everyone was just gripped by it and I thought I’d… not to sound like I’m blowing my own trumpet, but I’m a good page-turner; when I write I can keep you interested. And that’s a very derided quality in literary circles because it’s all about use of language. But I just kind of look at myself like Charles Dickens [Laughs]… if it’s a great story and I can tell it, then that’s brilliant..

So when did you last see Liam or Noel, and how did it go?

I saw Noel about two months ago at a friend’s surprise birthday party for his wife and it was great to see him. Unfortunately we were on different tables. But it was like, I walked in and I saw him sitting down, and he was talking to a couple of people. And he saw me and got up straight away and we shook hands. And I’m very much looking forward to hearing his album, I’ve heard good things about it. And the last time I saw Liam was probably 1998 or ’99 or something.

Right OK. A long time ago. And one final question: would you write about Oasis again? Is there another story to tell?

No. No. It’s like, you know the Beatles was – really – 1966 to ’69, d’you know what I mean? That was the real core of it, that was the real core of Oasis: ’94 to ’97. I think that’s the real core. I’m sure… I mean [Alan] McGee was telling me that their last album [2008’s Dig Out Your Soul] was a psychedelic masterpiece. Do you think that?

No. It’s good in parts; the bits I like, I like, but I don’t listen to all of it. Seeing them on that last tour was still incredible and the amazing thing, for me, was seeing 18 year-olds down the front who knew the words to Supersonic and I remember thinking, “You weren’t born when that came out!” That’s the power of the music, isn’t it? It’s like the Who or something.

Yeah. It is, they’re absolute classics. I think Don’t Look Back in Anger is a classic pop single, I really do: it’s up there with the Kinks, the Beatles. One of my favourite memories was when we were in Chicago and we went to this gig and we were in this coach afterwards. And they’d just got the tape of Top of the Pops that they’d done it on. And Noel’s wearing a white shirt and it just looked great. It looked fantastic and just everything you wanted. It looked great, you could tell that they were really together. I’ll always remember that moment. I remember thinking, “God, yeah, you’ve really done it.”

Paolo it’s been really great to talk to you.

It’s been great man, I’ve really enjoyed it. Thanks!

Paolo Hewitt was interviewed by Tom Stroud on 20th January 2015. Interview arranged, plus additional research & online presentation by David Huggins. The e-book of Paolo Hewitt’s Getting High: The Adventures of Oasis is out 2nd February 2015. Visit Paolo Hewitt’s website here.

Notes

Oasis live at the Cliffs Pavilion, Southend-On-Sea, 17th April 1995

1. (Back to article) This gig, Tony McCarroll’s last with the band, was filmed by Nigel Dick for Squeak Pictures and released by Picture Music International [PMI] on VHS as Live by the Sea on 28th August 1995. The concert film was also released on LaserDisc in Japan and the UK, by PMI and Pioneer LDCE. In 2001 it was reissued on DVD by Big Brother Recordings in the UK and by Sony Music Entertainment in the US.

NME Review of the Irvine Beach, Glasgow gig

2. (Back to article) In his review of this gig (published in the NME on 29th July 1995), Keith Cameron described not only Oasis’s breathtaking performance but also a huge sing-along to a Beatles classic afterwards. “Hey Jude comes over the PA, as clear and loud and true as anything that had gone before. Obviously everyone sings it, word for word, na-na-na-na for na-na-na-bloody-na. And yes, it’s sheer magic. Strangers are smiling, friends are embracing, while lovers are frankly losing it in a big way.”

The influence of Axe Corner – Tortuga on Columbia

3. (Back to article) Columbia shares its chords and main melody with Axe Corner – Tortuga, an acid house track released by Palmares Records in 1991. Axe Corner was a group of Italian DJs and producers comprising Adriano Dodici, Alex Neri, Marco Baroni, and Pietro Pieretti. In the sleeve notes for the 20th anniversary reissue of Definitely Maybe, Noel Gallagher recalled that, “When we started, we didn’t have a lot of songs so we would jam out current Acid House favourites and fuck about. Columbia derived from one of those nights.” Tony McCarroll stated in his (2009) book Oasis: The Truth that Columbia was initially an instrumental that Oasis played at some of their early gigs, before lyrics were written for it during their spring 1993 recording session with the Real People in Liverpool (McCarroll, p. 86).

Columbia also reflects a trend in early ’90s dance music (popularized by tracks like the Orb’s Little Fluffy Clouds and Primal Scream’s Loaded) of including spoken-word samples; the first can be heard over the song’s intro, and the second is an excerpt of Tony Benn reading a passage from the Bible (taken from a radio broadcast the band stumbled across. Noel: “On the demo of Columbia there’s a snippet of Tony Benn talking. We were just flicking through the radio recording it, and he was on.”). The demo was given a multicultural twist by the addition of an (as yet unidentified) sample of what sounds like a Hare Krishna-type chant on the outro. The sampled chant and Tony Benn clip were left off the final mix of Columbia for Definitely Maybe, but are retained in the Eden Studios mix included on CD-3 of the album’s 20th anniversary reissue.

Neil Innes and Whatever

4. (Back to article) In a video recorded to promote the release of Oasis’s greatest hits CD Time Flies, Noel Gallagher recalls learning of the similarity between Whatever and Neil Innes’ song How Sweet to be an Idiot. Neil Innes spoke about this rights issue in an interview he gave to Transatlantic Modern magazine in 2013:

Neil: [Paul McCartney’s brother Michael] rang me up and said, “Have you heard Oasis’s latest record [Whatever]?” I said, “No.” He said that Nicky Campbell… had just played it back to back with How Sweet To Be An Idiot. He said, “They’re virtually identical at the beginning.” I said, “Oh, really?” And I thought no more about it. Then more people said something about it, and I thought, “Well, I better ring up EMI about it,” because they’d published it. Immediately, they said, “We’re on it! We’re already on it!” Apparently they settled out of court. [The Oasis camp] put their hands up and gave me a quarter of Whatever. It goes to EMI, where it’s then divided 50/50 between EMI and me. […]

But what was quite funny to me, was that there’s a trade paper here called New Musical Express—the NME—of which you should never underestimate. They put a headline up sort of saying, “Innes to Sue Oasis!” And you know, I thought, “What?” It said: “Neil Innes is to sue Oasis for Whatever” blah, blah, blah. And then in the smaller print, it said, “Well at least we think he is, because we rang him up and he wasn’t in. We assumed it’s because he’s in court with his lawyers.” [Laughter] So this is how to make a headline work and not have to put an apology in afterward.” (Innes, 2013).

The Real People credits

5. (Back to article) Chris Griffiths recalled in a 2009 interview for MOJO magazine that Rockin’ Chair was one of the tracks that was influenced by the Real People; this was reflected in an additional writing credit for C. Griffiths when the song was reissued in November 1998 as part of the Masterplan compilation CD.

Wibbling Rivalry

6. (Back to article) The journalist John Harris interviewed Noel and Liam at the Forte Crest Hotel, Glasgow on 7th April 1994, for an infamous article (entitled The Bruise Brothers) published in the NME on 23rd April 1994. This interview is perhaps best remembered for Noel and Liam’s argument over a punch-up that took place during a ferry crossing to the Netherlands in February of that year, which led to the band being prevented from playing a gig in Amsterdam; Harris summarized Noel and Liam’s disagreement over the event in his Britpop memoir The Last Party: “Liam celebrated his role as an uncontrollable libertine; Noel, taking issue with his brother’s pride in Oasis’s high jinx, insisted that attention be paid to nothing but the music” (Harris, p. 146). The tape recording of this interview was later edited and released in 1995 by Fierce Panda records as a CD single entitled Wibbling Rivalry, attributed to “Oas*s.” It became the highest-charting interview release in the UK, having reached number 52 on 25th November 1995.